By Brian Rogers

In the past decade or so, underwater lighting has moved to center stage for many boaters. Some like it for the entertaining spectacle it provides at anchor or underway, often changing colors and synced with music. Others point to additional security it offers at night. Then there are anglers who swear they catch more fish because the illumination draws the quarry in toward the boat.

For installers called upon to answer customers’ questions about the technology, Marine Electronics Journal turned to underwater lighting expert Brian Rogers. Much of the information should be of interest to boaters who are planning to have underwater lights installed in their current boats—or in their next ride. Below Brian discusses different material and design options for light hardware and making sense of various specifications, features and mounting considerations. Next week he’ll get into control choices and other topics.

Ocean LED E7 TH Multi

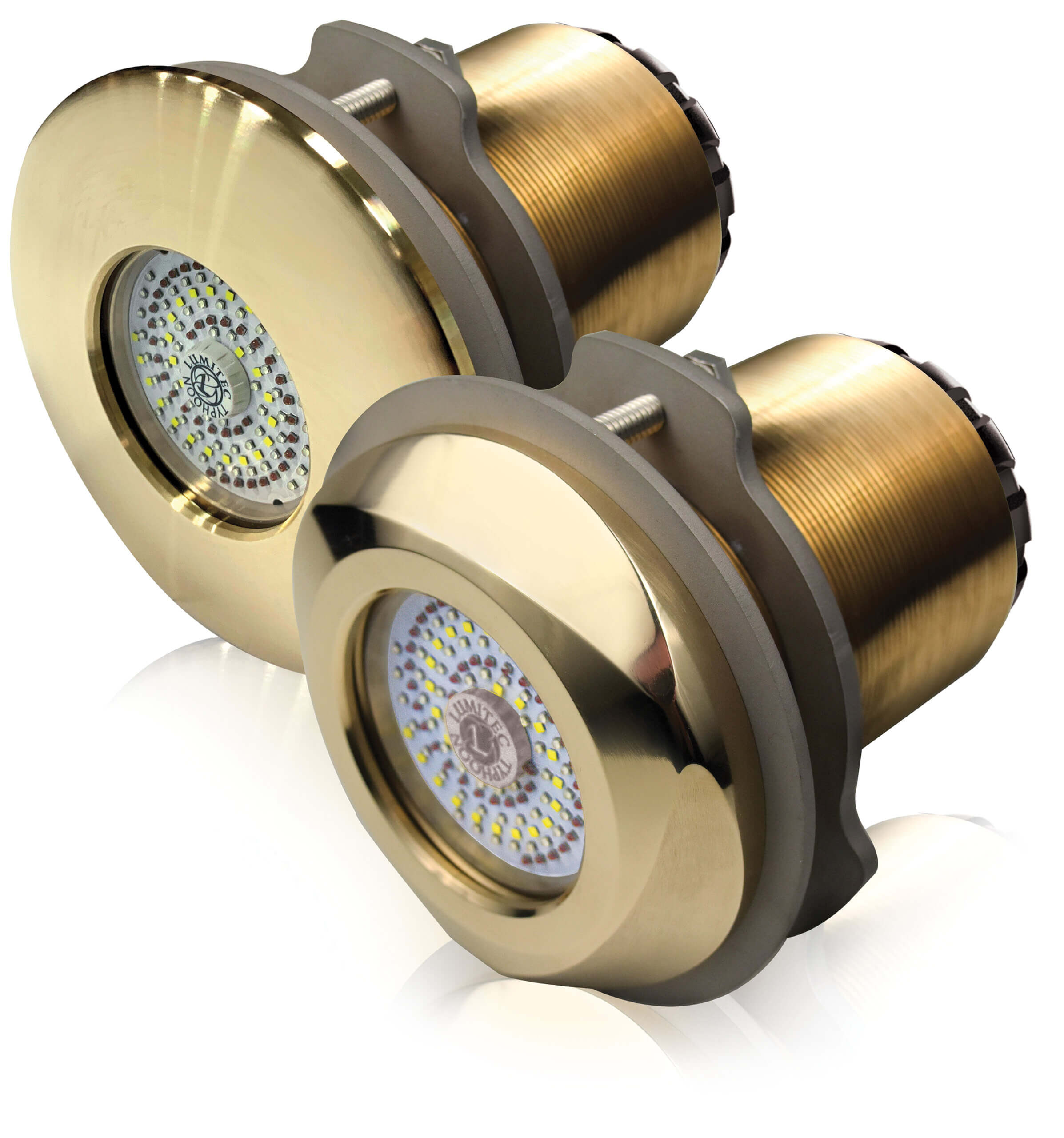

Lumitec Typhoon

Lumishore TIX803_EOS

Anybody who has spent time boating has probably seen underwater lighting in action. It adds a completely new dimension to boating, starting at the twilight hours and into the night. Before underwater lighting came along, the water around the boat at night was an abyss of darkness. Now, when properly lit, the abyss comes alive and adds a whole new dimension of excitement to the boating experience. Even murky waters light up beautifully. Underwater lighting properly executed in the clear Caribbean waters is a sight to behold.

There is no question why the demand is there for what has now become standard equipment for most new boats. However, for anyone charged with the responsibility of specifying, installing, or otherwise recommending these products, there is an overwhelming range of confusing options.

A quick Amazon or Google search for underwater boat lights brings up a dizzying array of sizes, shapes, styles, price ranges and brands. There are even certain fixture styles that are available from multiple “manufacturers.” Most of these supposed “manufacturers” are nothing more than marketing companies that source products from an actual manufacturer in Asia. They slap their name and logo on the product and present it to the market. Buyer beware. Do your homework if you are after a quality product. You must know who you are dealing with. Make sure they will be there if you have questions or need support after several seasons of boating and use of their products.

Material

What type of material is best for an underwater light? There is a range of options. The four main types are plastic (regular and thermally enhanced), aluminum, stainless steel, and bronze. Ultimately, the best choice comes down to budget, performance, boat type and the environment the boat will live in.

Plastic: Typically, this is the most budget-friendly option, and it’s seen a lot in smaller aluminum and pontoon boats. There’s a variety of small plastic underwater lights available that work well on smaller boats with tight spacing and budget requirements. Unfortunately, as these lights go up in size and brightness, their reliability tends to go down. This is due to plastic being a poor thermal conductor. Thermal conductivity is important because LEDs do not radiate heat in the same fashion that an incandescent light would. Instead, the wasted heat is conducted through the material and into the housing and ultimately into the water.

Longevity (lifetime of the actual LED) is directly related to time the LED spends at temperature. Run the LED too hot for too long and it dies an untimely death. Also, a cooler LED is brighter and more energy efficient. This is a good time to point out that a lot of higher power underwater lights are designed to only operate underwater. If you run them outside of the water for too long, they run the risk of what is referred to as “thermonuclear meltdown!” Always make sure that the product that you choose is protected against overheating.

Aluminum: If you desire a brighter light in the same amount of space as a plastic light, consider that aluminum is over 100 times more efficient at conducting heat than typical plastics, and at least 20 times better than most thermally enhanced plastics. Even though aluminum should always have some type of coating for protection of the bare metal, it is a good option for higher performance applications on pontoons and smaller boats. Aluminum lights will even work well for larger center console-style boats that are trailer and lift kept. Aluminum lights are not recommended for regular saltwater use. If the coating on the aluminum is scratched or compromised, it can lead to an entry point for corrosion and quickly become unsightly.

Stainless Steel: This material does not require coating as it is protected by its natural oxide layer. It is a great choice as it can be mirror polished to provide a very high-end look. (Specifically, SS316 is recommended for any application that will be exposed to saltwater, but less corrosion-resistant forms 303 and 304 can be found in some products as well.) Stainless steel is not recommended for applications where the boat will be kept in saltwater for extended periods of time, especially around marinas and possible sources of stray current. Stray current can cause one end of the stainless light to act as an anode and leach out ferrous content and exhibit unsightly surface rust.

Bronze: For larger fiberglass boats living in freshwater, aluminum is acceptable, but often bronze is a better option as it is much better suited for saltier environments. Larger boats that will live in the water full time are generally recommended to use a bronze product. As such, most quality boat manufacturers that produce vessels which are potentially used in saltwater specify bronze housing underwater lights. Bronze forms its own oxidation layer and can protect itself in corrosive environments without fragile coatings like those required on aluminum. The thermal performance of bronze is good, and generally recommended for larger “live-in-water” boats and boats that are regularly exposed to corrosive saltwater environments.

Shadow-Caster SC3

Aqualuma GEN4 6 Series

Mounting/mechanical design

Beyond checking to make sure that the light fits the footprint of the space you have for mounting it, in a fiberglass boat make sure that clearance exists on the inside of the transom and that you will not be drilling directly into a stringer or other unmovable object. There are a few other items to consider in this department as well. Is the mounting surface completely flat? Will the light be able to flex enough when mounting? If there is some gap left, will you be able to fill in the gap with sealant?

Are all of the electronics built into the light? Some manufacturers make nice, sealed fixtures, but then deliver a separate set of drive electronics in a housing that is completely unsealed. Unsealed electronics tend not to hold up well in the marine environment. Not only are these external drive electronics a common failure point, they’re also an additional headache to mount and wire.

NEXT WEEK: Optical and electrical specs and lighting controls

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brian Rogers has 25-plus years of experience in optical-electrical design. He obtained his BS in EE from the University of Central Florida and spent 15 years in product development before co-founding Shadow-Caster. Rogers chaired the NMEA 2000 Lighting Standard PGN development team and uses these PGNs today in Shadow-Caster products. Most weekends he cruises the Gulf with his family.